One filing error costs law firms an average of $53,000 in dismissed cases annually: improper service of process. When a California tech company failed to serve documents within the state’s 60-day window, the entire case was thrown out after eight months of preparation. The opposing counsel walked away, and the plaintiff lost their chance at recovery.

Service of process standards exist to protect constitutional due process rights by ensuring defendants receive proper notice of legal proceedings. In Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., the Supreme Court established that notice must be “reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties of the pendency of the action.”

This guide covers everything legal professionals need to know about service requirements, from federal baselines to state-specific variations, helping you avoid costly mistakes that derail cases before they begin.

What Is Service of Process?

Service of process is the legal procedure for delivering court documents to notify parties of legal action against them. Without proper service, courts cannot exercise jurisdiction over defendants, making it the foundation of every lawsuit.

Valid service requires three core elements:

- Authorized personnel – Documents must be delivered by legally qualified servers

- Proper recipients – Service must reach the correct individual or entity

- Approved methods – Delivery must follow court-accepted procedures

After completing service, the server must file proof of service with the court, creating an official record that service occurred correctly.

Federal Service Standards

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 4 establishes baseline requirements for federal cases. Key provisions include:

Time Limits: Plaintiffs must serve defendants within 90 days of filing the complaint. Federal courts may dismiss cases without prejudice if this deadline isn’t met.

Who Can Serve: Any person who is at least 18 years old and not a party to the case may serve process. This includes professional process servers, sheriff’s deputies, or any non-party adult.

Service Methods for Individuals:

- Personal delivery to the defendant

- Leaving copies at the defendant’s dwelling with a person of suitable age and discretion

- Delivering to an authorized agent

- Following state law, where the court sits or where service occurs

Waiver of Service: Federal rules encourage defendants to waive formal service. Plaintiffs can mail a waiver request, and if accepted, both parties save time, and the defendant gets extra time to respond.

State-Specific Requirements

State service standards vary significantly. Understanding local rules is essential for compliance.

California Standards

California imposes strict timelines based on case type:

General Civil Cases: Service must occur within 60 days of filing. If the plaintiff cannot show good cause for delay beyond this period, courts may dismiss the case.

Small Claims Cases: Timeline varies by defendant location:

- 15-20 days before hearing for in-county defendants

- Additional time for out-of-county service

Unlawful Detainer (Eviction): Service required within 5 days due to the expedited nature of housing proceedings.

Licensing Requirements: Process servers who serve more than 10 documents annually must register with the county clerk and post a $2,000 surety bond.

New York Standards

New York requires service within 120 days of filing for most civil cases. The state mandates personal service for many case types, though substitute service is available when personal service proves difficult after reasonable attempts.

Texas Standards

Texas allows 90 days for service in most civil cases. The state permits service by certified mail, return receipt requested, in addition to personal service—offering more flexibility than some jurisdictions.

Who Can Serve Legal Documents?

Server qualifications matter. Most states require:

Minimum Requirements:

- At least 18 years old

- Not a party to the case

- Mentally competent

Professional Requirements: Many states add certification or licensing requirements for professional servers. These standards ensure qualified individuals handle document delivery and maintain industry professionalism.

Prohibited Servers: Parties to the lawsuit cannot serve their own documents. This prevents conflicts of interest and ensures neutral delivery.

Acceptable Service Methods

Courts recognize several service methods, each with specific requirements:

Personal Service

Direct hand delivery to the defendant remains the gold standard. The server physically hands documents to the individual, confirming their identity when possible.

Substitute Service

When personal service fails after reasonable attempts (typically 3-5 tries), substitute service may be available:

- Leave documents with a competent adult at the defendant’s residence

- Post at the residence and mail copies

- Deliver to the defendant’s workplace

Requirements vary by state, and servers must document all personal service attempts before using substitute methods.

Service by Mail

Some jurisdictions permit service by certified or registered mail. California allows this for certain case types, requiring a return receipt to prove delivery.

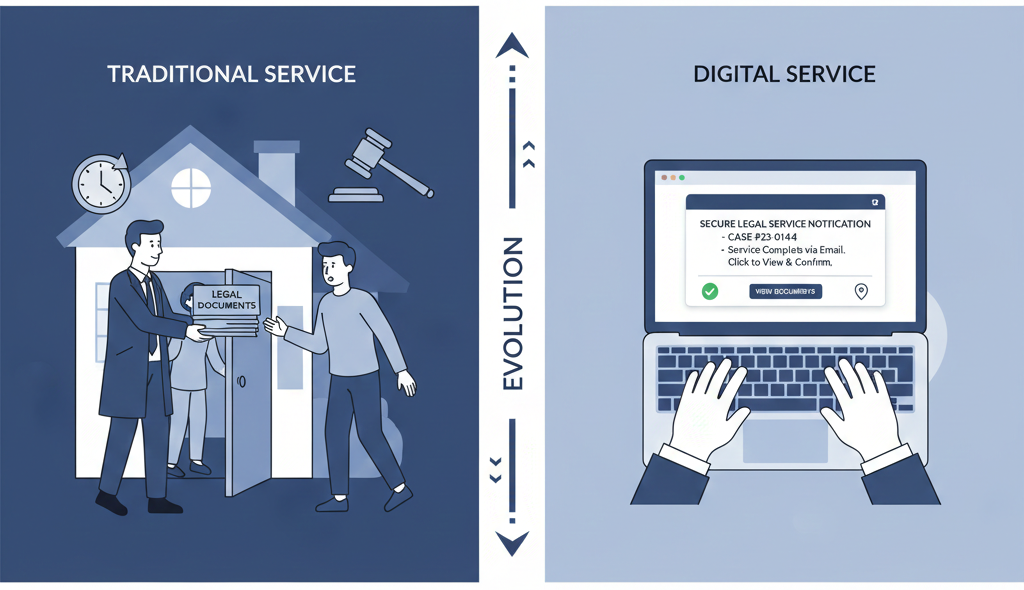

Electronic Service

Digital delivery methods are gaining acceptance. Many jurisdictions now permit service via secure email or dedicated portals when:

- Both parties consent to electronic service

- The method ensures the authentication of the recipient

- The system provides reliable proof of transmission

Courts expanded electronic service options during COVID-19, and many jurisdictions have maintained these alternatives.

Documentation Requirements

Proper documentation protects service validity if challenged in court.

Proof of Service

Every service requires a proof of service (also called an affidavit of service or return of service) that includes:

- Date and time of service

- Location where the service occurred

- Method used (personal, substitute, mail, etc.)

- Name of person served

- Server’s signature and declaration under penalty of perjury

Service Attempt Logs

Professional servers maintain detailed logs documenting:

- Each service attempt date and time

- Location visited

- People contacted

- The reason the service wasn’t completed

- Description of the premises

This documentation becomes vital when explaining why substitute service is necessary or defending service validity.

Photographic Evidence

Many professional servers now use digital photography to document:

- The location where the service occurred

- The person served (when appropriate)

- Posted service notices (for posting and mailing methods)

Photos provide visual evidence supporting written affidavits.

Common Service Challenges

Evasive Defendants

Defendants who actively avoid service create significant challenges. California law doesn’t set an official limit on service attempts, but most servers make 3-5 attempts at different times and days before pursuing substitute service.

Strategies for evasive subjects:

- Vary service attempt times (morning, afternoon, evening)

- Try different days of the week

- Check multiple known locations

- Use skip tracing to identify current addresses

- Document all attempts thoroughly

Corporate Service

Serving business entities requires specific knowledge:

Registered Agent Service: Most states require corporations to maintain a registered agent for service of process. This provides a reliable service point.

Corporate Officer Service: When registered agent service isn’t available, documents may be served on specific corporate officers depending on state law.

Virtual Office Challenges: Companies using virtual offices or coworking spaces complicate service. Servers must determine actual business locations and identify appropriate recipients.

Multi-State Service

Cross-jurisdictional service requires understanding:

- Service requirements in both the filing state and the service state

- Interstate service agreements

- Federal long-arm statutes

- International service treaties (for overseas service)

Quality Assurance Best Practices

Professional process serving companies implement quality controls:

Pre-Service Verification

Before attempting service:

- Verify current addresses through database searches

- Confirm corporate status and registered agents

- Review case-specific service requirements

- Identify any special circumstances

Multi-Point Review

Quality systems include:

- Document review before service

- Real-time service confirmation

- Post-service documentation review

- Client communication at each stage

Continuing Education

Regular training keeps servers current on:

- Changing state and federal rules

- New court procedures

- Technology integration

- Professional ethics

Professional Organizations and Standards

Industry associations establish standards exceeding minimum legal requirements:

National Association of Professional Process Servers (NAPPS): Sets ethical guidelines, provides training, and advocates for professional standards.

State Associations: Many states have local organizations offering region-specific education and networking.

Membership signals commitment to professional excellence and provides access to continuing education resources.

The Future of Service Standards

Expanding Electronic Options

Courts continue to broaden electronic service acceptance. Expect:

- More jurisdictions are allowing email service

- Secure portal systems for document delivery

- Blockchain-based proof of service systems

- Video-confirmed service methods

Greater Standardization

Professional organizations work toward consistent requirements across jurisdictions, reducing complexity for multi-state servers while maintaining local protections.

Enhanced Security

As cyber threats grow, service standards increasingly address:

- Encrypted document transmission

- Multi-factor authentication for electronic service

- Secure chain-of-custody documentation

- Protection of sensitive case information

Conclusion

Service of process standards form the foundation of due process rights and fair legal proceedings. Proper service requires understanding federal baselines, state-specific variations, acceptable methods, and documentation requirements.

Working with experienced legal support services ensures your documents are served correctly, avoiding delays, dismissals, and jurisdictional challenges. Whether handling routine service or complex multi-jurisdictional cases, compliance with service standards protects your clients’ interests and keeps cases moving forward.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What happens if service of process isn’t completed correctly?

Improper service can lead to serious consequences: case dismissal, delayed proceedings, or challenges to the court’s jurisdiction. Courts may require re-service using proper methods, which impacts case timelines and strategy. In some cases, defendants can move to quash service, forcing plaintiffs to start the service process over—potentially missing statute of limitations deadlines.

2. How long do I have to serve legal documents?

Service deadlines vary by jurisdiction and case type:

- Federal courts: 90 days from filing

- California civil cases: 60 days from filing

- California unlawful detainer: 5 days from filing

- New York civil cases: 120 days from filing

- Texas civil cases: 90 days from filing

Always check specific court rules for your case type and jurisdiction.

3. Can I serve legal documents myself?

No, parties to a lawsuit cannot serve their own documents. You must be at least 18 years old and not involved in the case. You can hire a professional process server, use a sheriff’s office, or ask any qualified adult who isn’t a party to serve documents on your behalf.

4. What’s the difference between personal and substitute service?

Personal service means handing documents directly to the defendant. Substitute service is used when personal service fails after reasonable attempts—typically leaving documents with another adult at the defendant’s home or workplace, often combined with mailing copies. Substitute service has stricter requirements and usually requires court approval or documented service attempts.

5. Is electronic service of process legally valid?

Yes, in many jurisdictions, but with conditions. Electronic service typically requires:

- Consent from both parties

- Use of secure, authenticated delivery systems

- Proof of transmission and receipt

- Compliance with specific court rules

Not all case types permit electronic service, and requirements vary by jurisdiction. Always verify local rules before relying on electronic methods.

6. How much does professional process service cost?

Costs vary by location, case complexity, and urgency:

- Routine service: $45-$95 per service

- Rush service: $100-$200+

- Skip tracing (locating defendants): $75-$300

- Corporate service: $75-$150

- Out-of-state service: $100-$300+

Many process servers charge extra for multiple service attempts, weekend service, or difficult-to-serve defendants.

7. What qualifications should I look for in a process server?

Look for:

- Proper state licensing or registration (where required)

- Professional liability insurance

- Surety bond (required in many states)

- Membership in professional organizations like NAPPS

- Experience with your specific case type

- Knowledge of local court rules

- References from attorneys or law firms

8. Can a process server leave documents at my door?

Usually not as a first option. Most states require personal service or proper substitute service. Simply leaving documents at a door without following specific procedures typically isn’t valid service. However, some jurisdictions allow “nail and mail” service (posting documents and mailing copies) as a form of substitute service after personal service attempts fail.

9. What if the defendant refuses to accept the documents?

Refusal doesn’t prevent valid service. If a process server clearly identifies the person and attempts to hand them documents, the service is complete even if the person refuses to take the papers—the server can set them down near the person. However, the server must properly identify the individual first. Simply throwing papers at someone who won’t identify themselves doesn’t constitute valid service.

10. How do I serve someone in another state?

Interstate service options include:

- Hire a process server licensed in the state where the defendant lives

- Use the court system in the defendant’s state

- Follow Federal Rule 4 for federal cases

- Comply with both your state’s rules and the service state’s rules

- Consider interstate service agreements between states

For international service, follow the Hague-Visby Service Convention procedures.